We are sharing here an essay by Wyatt Mason first published under the title “Very Like a Whale: Extracts on Friendship (Compiled by a Sub-Sub-Librarian)” in volume twelve, “On Friendship,” of the Journal of the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard College. On the July 25, 2025, episode of The World in Time, Mason spoke with Donovan Hohn about the curious documents, “Etymologies” and “Extracts,” that precede the famous first sentence of Melville’s novel. Because Mason’s essay is kindred to the Extracts we’ve published on Substack this summer, we asked his permission to share it here, as this week’s installment—a return to the topic of Friendship, yes, but Friendship is a topic to which one might keep returning.

There might have been a time, not so long ago, when a person who reads novels, if asked, could have been depended upon to supply from memory the first line or lines of their favorites. Such a reader might have said: “It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.” Or, they might have said: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Maybe they would have said: “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins.” And if they had begun with any of these, they might have gone on to say: “Oh, well, I mean, ‘Call me Ishmael,’ of course, but that sort of goes without saying.”

I think it also goes without saying (and yet here I am, saying it) that the time during which we could have depended upon the reader of novels to have a brace of first lines at the ready may have passed. If we focus, then, on the oddball or two who could confidently offer, now, if asked, as a first response, “Call me Ishmael,” I regret to be the pedant who would say: well, no, that’s not the first line of Moby-Dick.

Actually, that great novel begins with this line: “It will be seen that this mere painstaking burrower and grub-worm of a poor devil of a Sub-Sub appears to have gone through the long Vaticans and street-stalls of the earth, picking up whatever random allusions to whales he could anyways find in any book whatsoever, sacred or profane.” And, because to cut off Melville at any point risks raising him, reasonably, from the dead, let him have his say, from deep in the public domain:

Therefore you must not, in every case at least, take the higgledy-piggledy whale statements, however authentic, in these extracts, for veritable gospel cetology. Far from it. As touching the ancient authors generally, as well as the poets here appearing, these extracts are solely valuable or entertaining, as affording a glancing bird’s eye view of what has been promiscuously said, thought, fancied, and sung of Leviathan, by many nations and generations, including our own.

So fare thee well, poor devil of a Sub-Sub, whose commentator I am. Thou belongest to that hopeless, sallow tribe which no wine of this world will ever warm; and for whom even Pale Sherry would be too rosy-strong; but with whom one sometimes loves to sit, and feel poor-devilish, too; and grow convivial upon tears; and say to them bluntly, with full eyes and empty glasses, and in not altogether unpleasant sadness—Give it up, Sub-Subs! For by how much the more pains ye take to please the world, by so much the more shall ye for ever go thankless! Would that I could clear out Hampton Court and the Tuilieries for ye! But gulp down your tears and hie aloft to the royal-mast with your hearts; for your friends who have gone before are clearing out the seven-storied heavens, and making refugees of long-pampered Gabriel, Michael, and Raphael, against your coming. Here ye strike but splintered hearts together—there, ye shall strike unsplinterable glasses!

Bona fides, essentially—preceding the real quarry of the white whale—with the understanding that there’s pleasure in the search, and in the tour of discoveries. Melville offered a dozen pages of fun, drawn from his reading and research, to get his novel underway, all of which inform our sense of the sources of, if not his book, the curiosity that we as a species have shown for those giants we glimpse with awe.

Herewith, then, extracts on a different subject in a similar mode. They precede no novel, except the one you yourselves might write: on friendship.

And the LORD spake unto Moses face to face, as a man speaketh unto his friend. (Exodus 33:11)

Now when Job’s three friends heard of all this evil that was come upon him, they came everyone from his own place; Eliphaz the Temanite, and Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite: for they had made an appointment together to come to mourn with him and to comfort him. (Job 2:11)

My friends scorn me: but mine eye poureth out tears unto God. (Job 16:20)

I behaved myself as though he had been my friend or brother: I bowed down heavily, as one that mourneth for his mother. (Psalms 31:14)

The offices of friendship are so numerous, and of such different kinds, that many little disgusts may arise in the exercise of them, which a man of true good sense will either avoid, extenuate, or be contented to bear, as the nature and circumstances of the case may render most expedient. But there is one particular duty which may frequently occur, and which he will at all hazards of offense discharge, as it is never to be superseded consistently with the truth and fidelity he owes to the connection; I mean the duty of admonishing, and even reproving, his friend, an office which, whenever it is affectionately exercised, should be kindly received. It must be confessed, however, that the remark of my dramatic friend is too frequently verified, who observes in his Andria that “obsequiousness conciliates friends, but truth creates enemies.” When truth proves the bane of friendship we may have reason, indeed, to be sorry for the unnatural consequence; but we should have cause to be more sorry if we suffered a friend by a culpable indulgence to expose his character to just reproach.

Upon these delicate occasions, however, we should be particularly careful to deliver our advice or reproof without the least appearance of acrimony or insult. Let our obsequiousness (to repeat the significant expression of Terence) extend as far as gentleness of manners and the rules of good breeding require; but far let it be from seducing us to flatter either vice or misconduct, a meanness unworthy, not only of every man who claims to himself the title of friend, but of every liberal and ingenuous mind. Shall we live with a friend upon the same cautious terms we must submit to live with a tyrant? Desperate indeed must that man’s moral disorders be who shuts his ears to the voice of truth when delivered by a sincere and affectionate monitor! It was a saying of Cato (and he had many that well deserve to be remembered) that “some men were more obliged to their inveterate enemies than to their complaisant friends, as they frequently heard the truth from the one, but never from the other;” in short, the great absurdity is that men are apt, in the instances under consideration, to direct both their dislike and their approbation to the wrong object. They hate the admonition, and love the vice; whereas they ought, on the contrary, to hate the vice, and love the admonition.

As nothing, therefore, is more suitable to the genius and spirit of true friendship than to give and receive advice—to give it, I mean, with freedom, but without rudeness, and to receive it not only without reluctance, but with patience—so nothing is more injurious to the connection than flattery, compliment, or adulation. I multiply these equivalent terms in order to mark with stronger emphasis the detestable and dangerous character of those pretended friends, who, strangers to the dictates of truth, constantly hold the language which they are sure will be most acceptable. But if counterfeit appearances of every species are base and dishonest attempts to impose upon the judgment of the unwary, they are more peculiarly so in a commerce of amity, and absolutely repugnant to the vital principle of that sacred relation; for, without sincerity, friendship is a mere name, that has neither meaning nor efficacy.

“On Friendship”

—Cicero (W. Melmouth, Tr.)

There seems to be nothing for which Nature has better prepared us than for fellowship—and Aristotle says that good lawgivers have shown more concern for friendship than for justice. Within a fellowship the peak of perfection consists in friendship; for all forms of it which are forged or fostered by pleasure or profit or by public or private necessity are so much the less beautiful and noble—and therefore so much the less “friendship”—in that they bring in some purpose, end or fruition other than the friendship itself. Nor do those four ancient species of love conform to it: the natural, the social, the hospitable and the erotic.

“On Friendship”

—Montaigne (M.A. Screech, Tr.)

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought I summon up remembrance of things past, I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought, And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste: Then can I drown an eye (unus’d to flow) For precious friends hid in death’s dateless night, And weep afresh love’s long since cancell’d woe, And moan th’ expense of many a vanish’d sight. Then can I grieve at grievances foregone, And heavily from woe to woe tell o’er The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan, Which I new pay as if not paid before. But if the while I think on thee (dear friend) All losses are restor’d, and sorrows end. Sonnet 30 —Shakespeare

I was angry with my friend: I told my wrath, my wrath did end. I was angry with my foe: I told it not, my wrath did grow. And I waterd it in fears, Night & morning with my tears: And I sunned it with smiles, And with soft deceitful wiles. And it grew both day and night. Till it bore an apple bright. And my foe beheld it shine, And he knew that it was mine. And into my garden stole When the night had veild the pole: In the morning glad I see; My foe outstretchd beneath the tree. “The Poison Tree” —William Blake

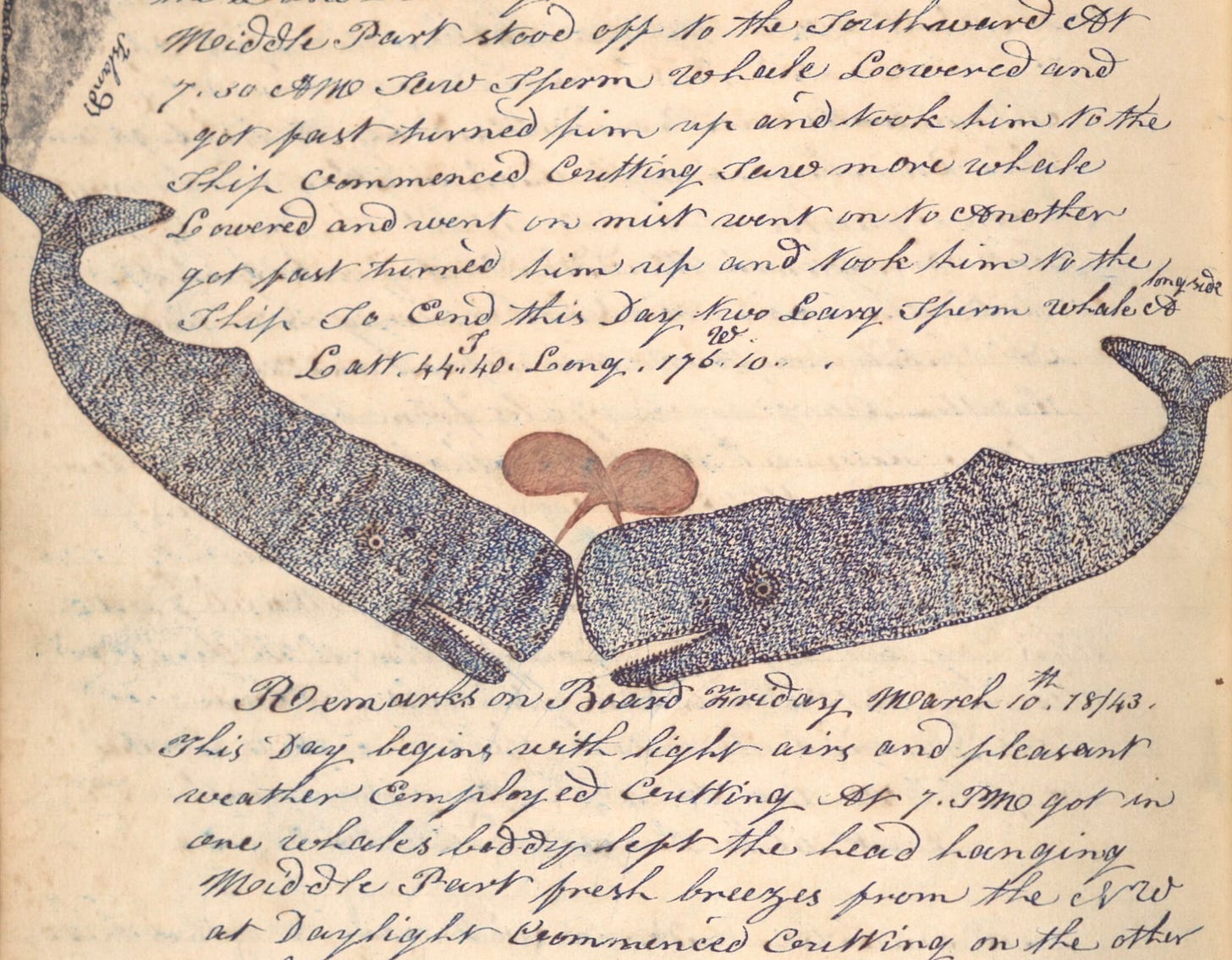

We then turned over the book together, and I endeavored to explain to him the purpose of the printing, and the meaning of the few pictures that were in it. Thus I soon engaged his interest; and from that we went to jabbering the best we could about the various outer sights to be seen in this famous town. Soon I proposed a social smoke; and, producing his pouch and tomahawk, he quietly offered me a puff. And then we sat exchanging puffs from that wild pipe of his, and keeping it regularly passing between us.

If there yet lurked any ice of indifference towards me in the Pagan’s breast, this pleasant, genial smoke we had, soon thawed it out, and left us cronies. He seemed to take to me quite as naturally and unbiddenly as I to him; and when our smoke was over, he pressed his forehead against mine, clasped me round the waist, and said that henceforth we were married; meaning, in his country’s phrase, that we were bosom friends; he would gladly die for me, if need should be. In a countryman, this sudden flame of friendship would have seemed far too premature, a thing to be much distrusted; but in this simple savage those old rules would not apply.

Moby-Dick, Chapter 10: “A Bosom Friend”

We have a great deal more kindness than is ever spoken. Maugre all the selfishness that chills like east winds the world, the whole human family is bathed with an element of love like a fine ether. How many persons we meet in houses, whom we scarcely speak to, whom yet we honor, and who honor us! How many we see in the street, or sit with in church, whom, though silently, we warmly rejoice to be with!

Read the language of these wandering eye-beams. The heart knoweth.

The effect of the indulgence of this human affection is a certain cordial exhilaration. In poetry, and in common speech, the emotions of benevolence and complacency which are felt towards others are likened to the material effects of fire; so swift, or much more swift, more active, more cheering, are these fine inward irradiations. From the highest degree of passionate love, to the lowest degree of good-will, they make the sweetness of life.

Our intellectual and active powers increase with our affection. The scholar sits down to write, and all his years of meditation do not furnish him with one good thought or happy expression; but it is necessary to write a letter to a friend,—and, forthwith, troops of gentle thoughts invest themselves, on every hand, with chosen words. See, in any house where virtue and self-respect abide, the palpitation which the approach of a stranger causes. A commended stranger is expected and announced, and an uneasiness betwixt pleasure and pain invades all the hearts of a household. His arrival almost brings fear to the good hearts that would welcome him. The house is dusted, all things fly into their places, the old coat is exchanged for the new, and they must get up a dinner if they can. Of a commended stranger, only the good report is told by others, only the good and new is heard by us. He stands to us for humanity. He is what we wish. Having imagined and invested him, we ask how we should stand related in conversation and action with such a man, and are uneasy with fear. The same idea exalts conversation with him. We talk better than we are wont. We have the nimblest fancy, a richer memory, and our dumb devil has taken leave for the time. For long hours we can continue a series of sincere, graceful, rich communications, drawn from the oldest, secretest experience, so that they who sit by, of our own kinsfolk and acquaintance, shall feel a lively surprise at our unusual powers. But as soon as the stranger begins to intrude his partialities, his definitions, his defects, into the conversation, it is all over. He has heard the first, the last and best he will ever hear from us. He is no stranger now. Vulgarity, ignorance, misapprehension are old acquaintances. Now, when he comes, he may get the order, the dress, and the dinner,—but the throbbing of the heart, and the communications of the soul, no more.

What is so pleasant as these jets of affection which make a young world for me again? What so delicious as a just and firm encounter of two, in a thought, in a feeling? How beautiful, on their approach to this beating heart, the steps and forms of the gifted and the true! The moment we indulge our affections, the earth is metamorphosed; there is no winter, and no night; all tragedies, all ennuis, vanish,—all duties even; nothing fills the proceeding eternity but the forms all radiant of beloved persons. Let the soul be assured that somewhere in the universe it should rejoin its friend, and it would be content and cheerful alone for a thousand years.

“Friendship”

I know nothing—nothing in the world—of the hearts of men. I only know that I am alone—horribly alone. No hearthstone will ever again witness, for me, friendly intercourse. No smoking-room will ever be other than peopled with incalculable simulacra amidst smoke wreaths. Yet, in the name of God, what should I know if I don’t know the life of the hearth and of the smoking-room, since my whole life has been passed in those places? The warm hearthside!

The Good Soldier

—Ford Madox Ford

“I know it’s worse for you,” she said kindly. “We were married, but that was so long ago. And after it was over, nothing. No friendship, no contact, nothing. That’s how it had to be. And I’ll be honest, at first I thought I wouldn’t even go to the memorial.

“But then I thought, you know, closure. Whatever that means.”

When it’s suicide, someone at the memorial said, there can be no closure.

“But you,” she said. “You two were such good friends for so long. How I used to envy that. I used to think, if only he and I hadn’t fallen in love, then we could have had a friendship like that!”

But there’d been no resisting, had there. A love so potent it might have been the effect of a spell. One of those grand passions given only to some to experience, the rest to hear tell and dream about.

Even now it has the force of legend for me: beautiful, terrible, doomed.

I remember when being near the two of you was like being near a furnace. And I remember thinking, when things went wrong, that one or the other of you was going to end up dead. You yourself said it sometimes felt like you were doing something forbidden, even criminal. And she, raised Catholic, was convinced that such idolizing love had to be a sin. And, of course, in the end it was this that drove Wife Two to despair: not all your womanizing but the belief that such love doesn’t come twice in a life, that whatever you felt for her could not equal what you’d felt for Wife One, who, she would always fear, still had your heart. If only we hadn’t fallen in love: she said it over and over.

The Friend

—Sigrid Nunez

Wyatt Mason

Wyatt Mason is a journalist, essayist, critic and translator. His work has been published in Harper’s, The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, GQ, Esquire, and The New York Times Magazine, where he is a contributing writer. His journalism has won the National Book Critics Circle Nona Balakian Prize and a National Magazine Award. His translations of the complete works of Arthur Rimbaud are published by the Modern Library in three volumes. He teaches for the Bard Prison Initiative and is a writer in residence at Bard College, where he has taught since 2010 and he serves as a senior fellow at the Hannah Arendt Center.

Lapham’s Quarterly is a project of the American Agora Foundation, which is dedicated to fostering an appreciation of, and acquaintance with, the uses and value of history. Please help us continue our work. Donate today.